SPX Haul 2025: Reviews Part 1

In this installment: a full-length review of Allodynia

Back in September, I traveled down to Bethesda, Maryland and picked up a whole host of comics. Some are long, some are short. Not sure if all are good as I haven't read most of them. That's what we're here to find out. As I read through my pile, I'll be typing up reviews and sending them out. Some installments might have a few, some may have one. All depends on how much I feel I need to write and how many I've read.

To kick things off, I reviewed one of the few - maybe the only - Ignatz winner I picked up at the con.

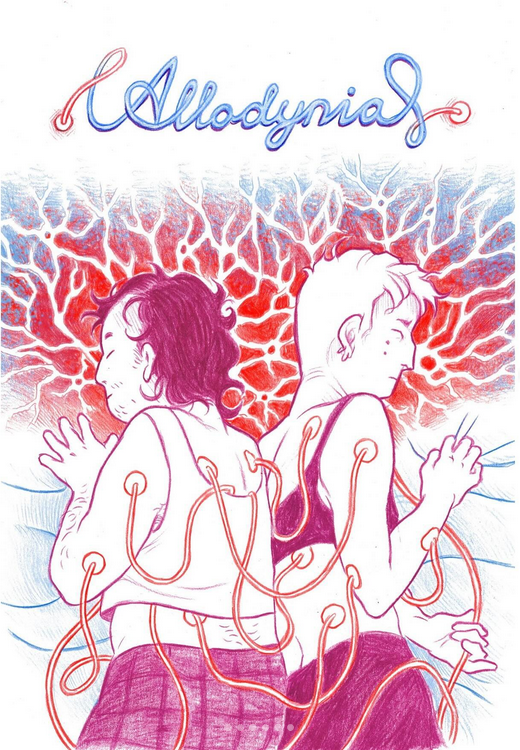

Allodynia

This was one of the books I was looking forward to picking up before getting onto the show floor. I missed it initially during the Shortbox Comics Fair and seeing it pop up on as one of the Ignatz nominees jogged my memory. “Allodynia” by Violet Kitchen follows Tess as they partake in a new medical experiment about pain, the details of which are left vague.

Much of the comic operates in this miasma of vagueness, fittingly for a comic about pain. Pain is so personal, so internal, and that’s something the comic explores through the fractured relationship between Tess and their partner, a wonderfully layered depiction of fear, stubbornness, distrust, and privilege. It is a frustrating read (complimentary) as I found myself see-sawing between both parties, angry and happy and sad at each in turn. I nearly yelled aloud a couple of times, seeing the train slowly come off the tracks.

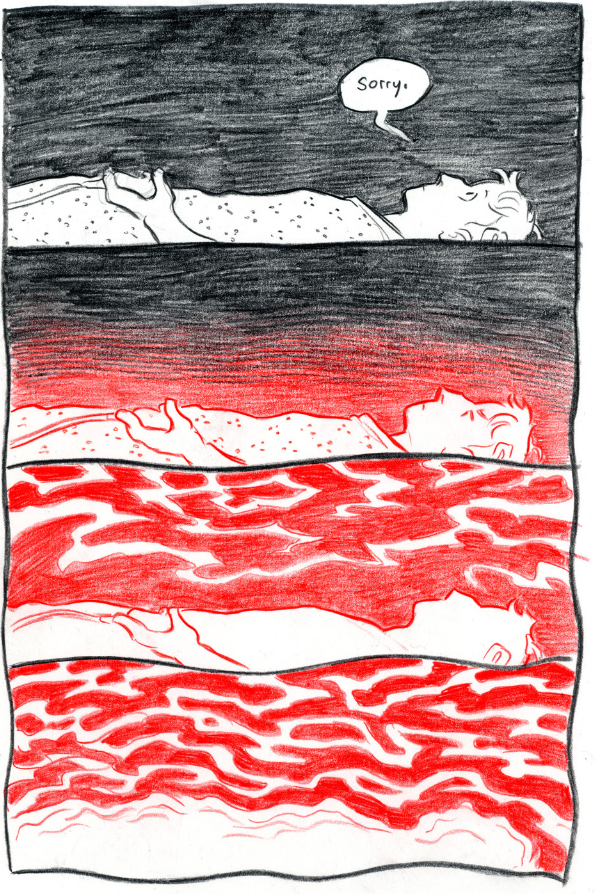

Kitchen’s art is wonderfully clear throughout. I love how the flashbacks wove in and out, colored in purple to distinguish it from the present. You get the sense that it’s what’s on their mind, particularly when the scenes are contained within Tess’ silhouettes and the ever growing thorns of red pain that accompany them.

There was also something to reading the comic as a spiral-bound book. The tactility of the paper and the presentation gave it an added heft, helped along by it being a 100ish page not-so-minicomic.

I must admit, and I’m probably showing my whole ass as a critic here, I didn’t “get” the ending, at least not initially. I re-read it a number of times and struggled to parse the meaning behind the final few pages. Is it hopeful? Are we to assume Tess understands better what their partner was saying when they fought just a few pages back? Or is it tragic? Representative of the cyclical nature of hurt? Was there a transference of pain? The sci-fi nature of the concept - the seemingly literal taking on of others’ pains - means I can grasp in many directions and none seem too far-fetched.

After sitting with it and mulling it over, I think I’ve found a reading I like, helped along by the blurb on the back. One’s pain- physical, mental, emotional - is so personal as to be unknowable to everyone around you. It is only in the expression of pain that it can be noticed. Even then, feeling, understanding, is so foreign as to be functionally unattainable. It's all just a guess. Like the limit of X, one can only ever approach it, never reach it, boomeranging to infinity.

Tess’s relationship to pain is abstract. They move through life without it, or with minimal awareness of it. Their partner Jules on the other hand, and the many, many, many, many, many others Tess encounters at their job, have some reminder of pain, be it constant and intense (like Jules’s fibro) or fleeting and acute. They live with it and manage it. As the comic progresses, Tess becomes physically aware of others’ pain, subsuming it into themself. Or, perhaps, they are simply more in tune with their own everyday aches and pains, magnified and compounded with each reminder.

By the end, when Tess goes for a run out of anger and to escape the fight they were having, they’re pushing themself, the pain building and building, until it explodes in a moment of absolute clarity; the ever building cacophony of red, matted, disorderly pain lines coalesces into a mandala that radiates out from their core and they sit on the ground, looking up at the shadowed and featureless outline of their partner in the distance.

Normally, Tess would get up, but they don’t. They lie down, keeping eye contact with their partner. Yet Tess’ expression is hard to read. Is it accusatory? Confused? Sublimated? Distraught? I’m not sure. Whatever the case, there is an unambiguous note of clarity in it. It’s powerful and a fitting cap to the story. In that moment, they’ve come to understand - not just know about, not just feel - their partner’s relationship to pain. They get it.

They get it.

Comments ()