One Must Imagine Lagoon Boy Happy, Part 3

What price secrecy?

3. The Price of Secrecy

Of all the questions “Heroes in Crisis” poses in some way, intentionally or otherwise, I feel there’s one that gets the least exploration. It concerns Lois Lane and her subplot.

In it, Lois is leaked every confession, which are supposed to be 10,000% confidential, encrypted beyond measure, fully private and fully anonymous, presumably by the same person who murdered everyone at Sanctuary (the ostensible main plot.) She is mildly perturbed by the idea of publishing the information and gestures at the ethical conundrum before shrugging her shoulders, releasing the piece, and, implied in the article’s copy, some of the videos (or at least their content.) This all resolves when Superman gives a big speech in issue #5. It is barely mentioned again.

Perhaps because this subplot was quickly overshadowed within the narrative and within critical discourse; perhaps because it is a corollary to my earlier queries; or perhaps because it’s presented in the most galling way possible, one of the thorny questions at its heart is easily overlooked. Namely, what obligation do high profile figures have to bear their private lives and struggles for the public?

In the age of the internet, a private life is hard to come by. Doubly, triply so for the famous. Imagine, then, a world for which there were the famous and then there were the Supers. Scrutinized. Idolized. Larger-than-life, they are people no longer. Only symbols in the minds of the public. That is how we talk about DC characters anyway, yes?

More so than the House of Ideas, the Distinguished Competition is built of symbols. They cannot be your neighbor, your friend, that person you see at the coffee shop every other day. They must occupy an idealized, mostly unchanging space. They struggle, sure. They fail, yes, for a time. But in the end, what they embody, what they are reduced to, matters more than the messy, contradictory, personness of the character.

Symbols, in this way, are more easily polished to a sheen…and more easily tarnished.

It’s a truism that one can never fully understand another person, no matter how close you may be; there will always be corners kept secret, kept hidden, kept close; there will always be perspectives that one cannot express outside the synapses fizzing along inside one’s own mind. There remain gaps, filled in by our own preconceptions, judgements, guesses, and assumptions. The farther a person is from you, the more those gaps grow, until all that remains is the symbol. Tom King is a symbol. DC Comics is a symbol. Wally West is a symbol. Unique, uncomplicated, fragile.

The fragility of the symbol is why, in the minds of many of these Supers, Sanctuary should be kept a secret. What goes on at Sanctuary shows these characters at their most vulnerable. If a society is to conceive of them as “more than” - without flaws, problems, or questions - then any crack in that facade shatters the symbol we’ve crafted in our heads, and there’s no guarantee that what is reconstructed will be favorable.

It is, to be sure, bullshit that one must think about mental health, or even doubt, this way. However, it is our present reality. While we as society - America and globally - are far, far more open than we once were, there remains a stigma, powerful and insidious, which whispers loudly to all.

Let us step back. I began this section by asking about obligation. Who deserves to know all about the messy nooks and crannies in one’s head? Who deserves to know what Superman worries about when he’s flying around? What does the public deserve to know about Black Canary? From one perspective, the answer is nothing at all. It’s why paparazzi are so often derided and the archetype of the gossiping courtesan is a frequent target for dismissal, misogyny around the latter set aside.

The private lives of public figures should be none of our business. It shouldn’t matter if it's purely prurient and superficial - what The Question had for breakfast or what Batwoman thinks about bar soap - or more serious - how Wildcat’s latest hand operation went, how Superman’s family day was or how Constantine’s 15th attempt to quit smoking is going. If a public figure wants to keep something (or everything) private, that’s their prerogative. Just because there may be interest in knowing doesn’t make it ethical to disseminate that information.

However, there is an obligation placed on public figures to be transparent and available, more so than the guy who buys 17 boxes of Wheaties every day at the local grocery store, because they have power, cultural and otherwise. It matters what political figures think. It matters how they make or spend their money. From a purely journalistic point of view, accountability of the powerful is rooted in knowledge of both the public and private.

How far does that knowledge go, however? At what point does it cross back into the realm of the unethical?

Take Roy Harper and his heroin addiction. Under what circumstance is this knowledge important to be public? What aspects? To whom? To a local community? To friends and family? To a close confidant only? Why? What about any time spent in rehab, or leaving rehab? Is this a story that can be told by an interested third party or is it only his to tell? How much of what he can tell should he tell? Does he feel comfortable being that vulnerable? Is it ethical to pressure him to be open to the public?

I have no clear answers for these questions, in part because Roy is a fiction and in part because I don’t think there should be any. Privacy is not one and done, one size fits all. It is a constant reevaluation, changing with time, situations, people, and temperament.

In her piece, and in her conversations with Clark, Lois is also asking: “Must Sanctuary be secret?” We could also ask: what is the value of said secrecy? What harm does it perpetuate? What damage would be wrought in keeping it a secret and then having that secret come out? Secrets aren’t inherently wrong to keep or to have, even as so many dollar store shows use their mere existence for cheap drama.

Sanctuary has some very good reasons to remain completely off-the-grid and unknown: the threat of supervillain attacks, a breakdown in trust from its residents and users tied to its promise of anonymity and privacy. It also has plenty of reasons to be open about its existence, though definitely not its location. Secrecy breeds mistrust, even when done for good (or necessary) reasons. There’s a reason the “keeping a secret identity from a loved one” trope, a fertile source of narrative conflict, remains to this day, even in stories where it really doesn't make sense anymore.

To be secret is not, as Gandalf might say, to be safe. It may not be useful. It may cause more problems than it solves. Sanctuary must take that into account in all that it does and in all that it represents. What does it say about our heroes if they feel they must hide away an important part of their experience and pretend it does not exist? What does it say about us?

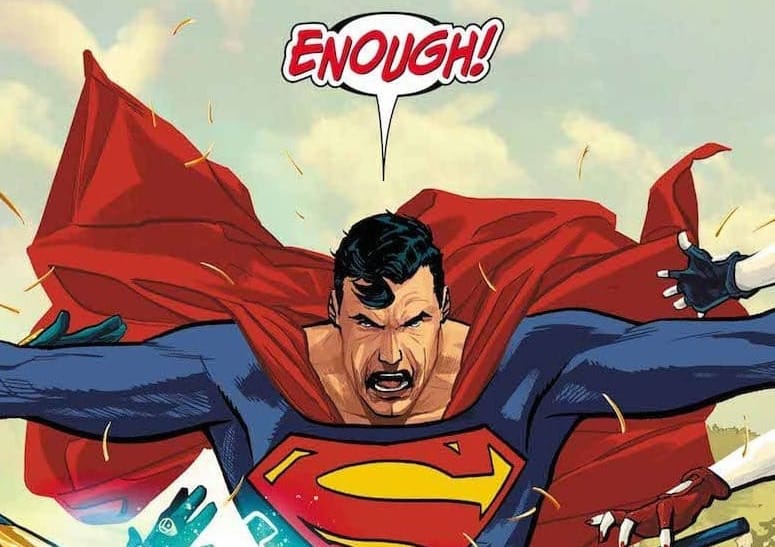

Superman is a symbol of hope and inspiration. He is sturdy and unflappable. Nothing seems to faze him and people look up to him, in part, for that reason. As a reader of a story, of course, we are privy to far more internality than the average Metropolitan on the street. We know he questions and struggles and is more than the big, blue blur. What, then, is more hopeful than Superman talking, publicly, about how he has doubts himself? How, when he’s feeling stressed, he goes to a place that is there to help. He talks about his problems. He learns about himself. He becomes better than he was because of this knowledge.

Is it not the duty of those with power to use it for good? Is it not doing good to dispel stigmas by demonstrating that, yes, Superman has struggles, just like you do, and yet the symbol has remained? Because if Superman is struggling, then maybe it’s OK for me to struggle too.

Liking what you read so far? Want these delivered straight to your inbox or, dare I say it, early? Sign up for a subscription today! I've got two tiers: free (newsletter access, basically) and the paid one (early access and whatnot.) Just $1.50 a month and you'll be supporting an independent writer.

If you aren't able to, that's OK as well. I'm just happy you're reading and sticking around. Alright. Back to the article.

The Myth of Sisyphus

Sisyphus pushes his rock up a hill. It is a large rock, taller than he is, just heavy enough to be a struggle but just light enough to be pushable. He toils and toils, slowly making progress on his task. After a time - it could be hours, it could be days, it could be weeks - he reaches the top. Then, cresting the hill, the rock begins its descent down, unaided by Sisyphus. The task, now completed, resets itself, and so Sisyphus must descend and begin his work anew.

Futility. That is the lesson of Sisyphus. Observe him and that is what you will discover. Observe longer and you will wonder why he does not give up. Why he does not stop, knowing it will never end. Knowing it will amount to nothing more than a rock going up, then coming back down, then going back up. DC fans, I’m sure, ask themselves these questions as well. DC creators, moreso. What is an 80-year old universe of characters, written yearly, monthly, weekly, if not a futile attempt to craft an ending that will stick?

Camus, famously, connected this myth, this retelling, to the absurdity of life in the modern world: a collection of tasks endlessly repeating with no external meaning behind them, ultimately coming undone as soon as they are finished and ready to be done again. Cycles of corporate comics in a nutshell. Miserable, yes? Yet it is our reality.

Some creators - Morrison chief among them, I’m sure - recognize this futility and imbue their work with the Absurd. They join Sisyphus in rolling his rock up that hill and, more crucially, in his descent back down, free from the task for a time before taking it up again. Think of what Sisyphus imagines during the brief time he is free of his task as the rock rolls back down. It is the only time that is truly his own, that his thoughts are wholly his own. As Camus says:

That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.

“Heroes in Crisis” takes these characters, these Sisyphuses, constantly pushing the rock, and gives us a glimpse into that hour of consciousness. Aware of this or not - considering the actual plot, not - King has turned them into Absurd heroes. Aware of the futility of their lives - fighting, dying, living, fighting, dying, living, fighting, dying, living - of the endless battles, with the same people, accomplishing the same goals, never growing, really; they sit and contemplate these truths.

Camus ultimately concludes that we must imagine Sisyphus happy, because the myth tells us nothing of Sisyphus’ time in the underworld. We do not get that luxury in the myth that is “Heroes in Crisis.” However, if “[m]yths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them,” then what must one do to breathe life into “Heroes in Crisis?” Into Wally and Gnarrk and Roy and Lagoon Boy?

Well, we must imagine them happy. In the moments we are not told about, in the moments they are lucid and free and able to focus on the meaning we imbue them with. That is all we can do. That is all we need to do.

All will be well.

Comments ()