One Must Imagine Lagoon Boy Happy, Part 2

The theological approach.

2. Confessions and Confidence

In colloquial American Jewish parlance, sanctuary has a number of different meanings. It is as described above but it is also a specifically religious locale located within the larger building. In “the main sanctuary” we congregate to say prayers, to worship. It is a site of communion with the divine, not just a refuge from the world outside. It even has its own additional sanctuary for the Torah scrolls. One goes to the sanctuary to converse and question and sing and, afterwards, have some nosh.

When one is in the sanctuary, it is customary to wear special garb - a tallis, tefillin, a yarmulke if not worn elsewhere - and often adjusts one’s clothes to be more traditionally modest. It is, however, multi-functional; additionally serving as a spot for community building and a communal space for gathering in joy and sadness. It is many things to many people but what it most is, at its best (and many are far from their best,) is welcoming, connecting, healing.

Most importantly for this piece, it is the workplace of our rabbis and cantors: our faith leaders. Don’t worry, I’m going somewhere with this.

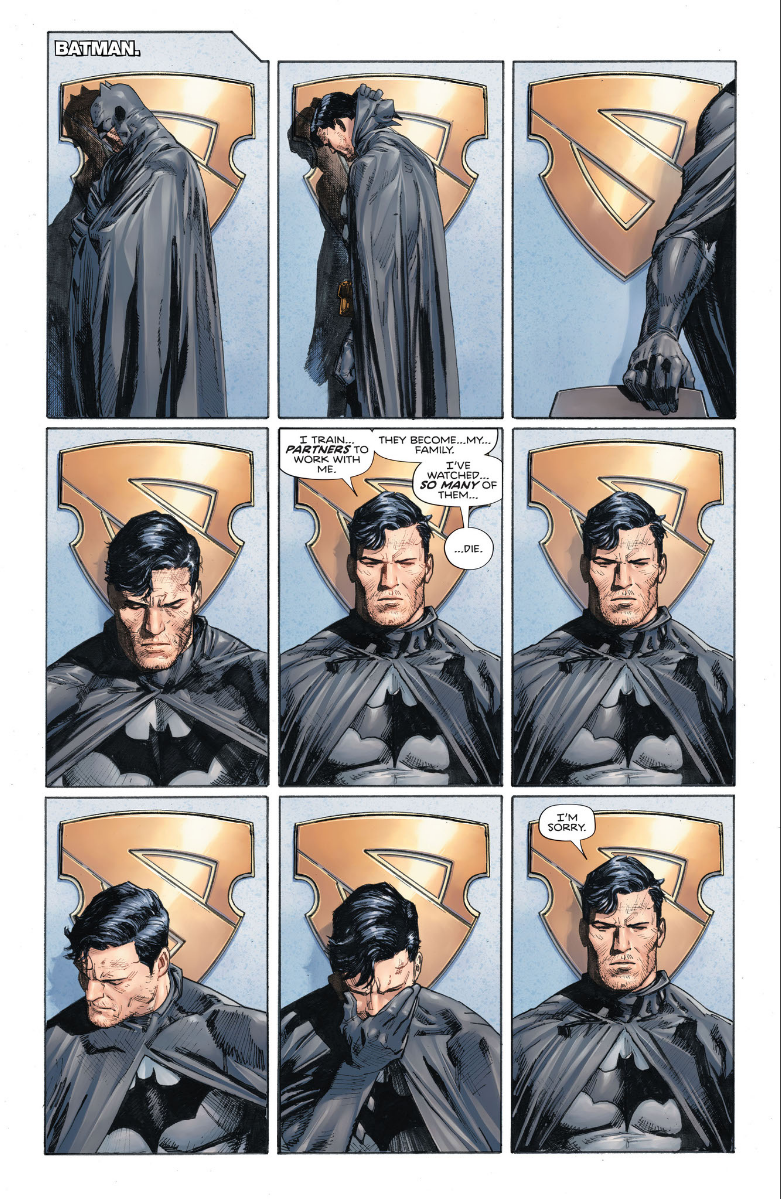

Historically, faith leaders have acted as confidants and therapists to their communities. Prior to the rise of secular psychiatry and therapy, these leaders would help people tackle thorny questions of faith and personal emotional struggles. They were the rocks, the solid centers of a village, an encampment, a neighborhood. To serve that role, it is not enough to be a person: one must instead be a symbol.

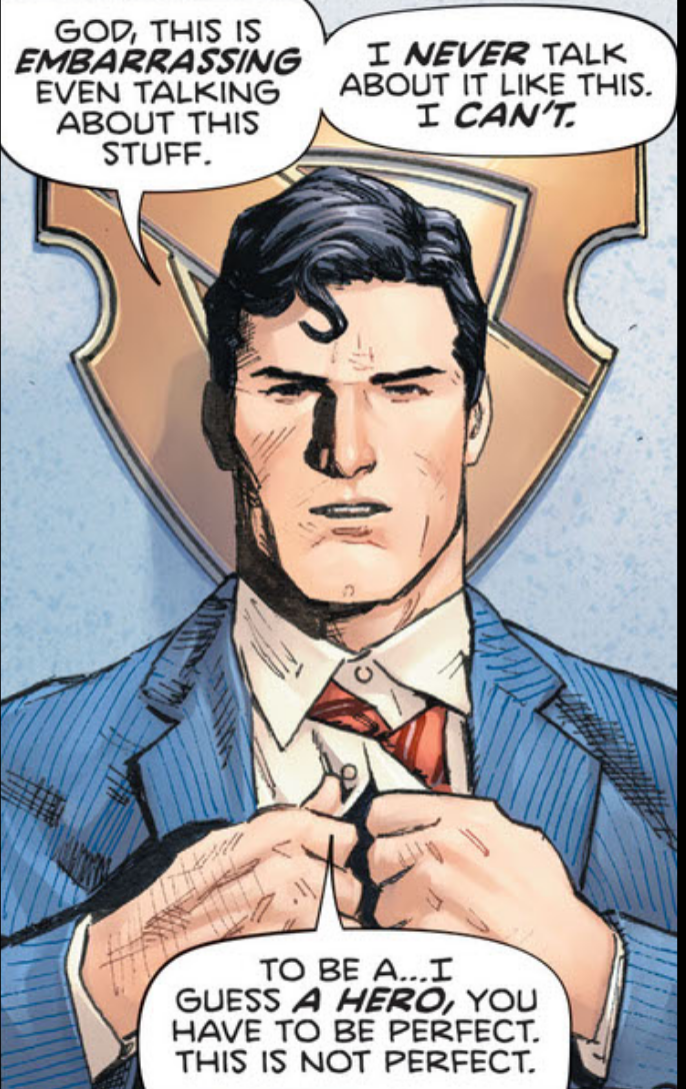

When you represent a higher power, your actions, your words, are no longer just your own. Who you are, to some extent, has to melt away, otherwise you risk losing the authority your role conveys. Yet you remain a person. You remain full of the same worries and questions and fears and struggles. You just can’t express it openly.

Let’s take this out of the religious and the historical. Think of your own family or friend group. Isn’t there at least one person everyone goes to? One person you feel comfortable talking to at length and in depth about their fears, their woes, their constant nagging questions about worth? Don’t you subconsciously see them as somehow different? Somehow “freed” from the burdens you feel yourself, which allows you to trust them with your own?

These are the people who are expected, rightly or wrongly, to be “more.” More approachable. More open. More “put together.” To break the facade and reveal oneself as fully, fallibly human destroys this specific form of trust between the parties. Whether this is actually true or not is an entirely different matter to whether it feels true. Perception is the whole ballgame, in this matter.

It is taxing, being a symbol. Don’t just take my word for it: take the Puritans; or, more specifically, take one Puritan: Thomas Shepard. He was a faith leader and famous preacher in 17th century New England and his diary has survived to this day, though it is better classified as a “spiritual journal.” There is little in the way of everyday diary stuff - weather, daily habits, scripture. Instead it is filled with more personal thoughts: repressed fantasies (highly tame by today’s standards) and other thoughts & acts perceived as sinful, doubts about God’s existence or benevolence, intrusive thoughts, and existential anxieties about the community’s well-being vis-a-vis a bad winter.

Most tellingly, however, it also includes the occasional lamentation on a lack of peers to talk to about these semi-private thoughts - particularly the more religiously contentious - constrained as he is by his position: a professional in a professional setting; 24/7; 365 days a year. It weighs on him and one can see the negative effects of this weight in other passages throughout. (If you’d like to read the full contents, check out God’s Plot: The Paradoxes of Puritan Piety: Being the Autobiography & Journal of Thomas Shepard, edited by Michael McGiffert.)

Which brings us, finally, back to our heroes and their crises.

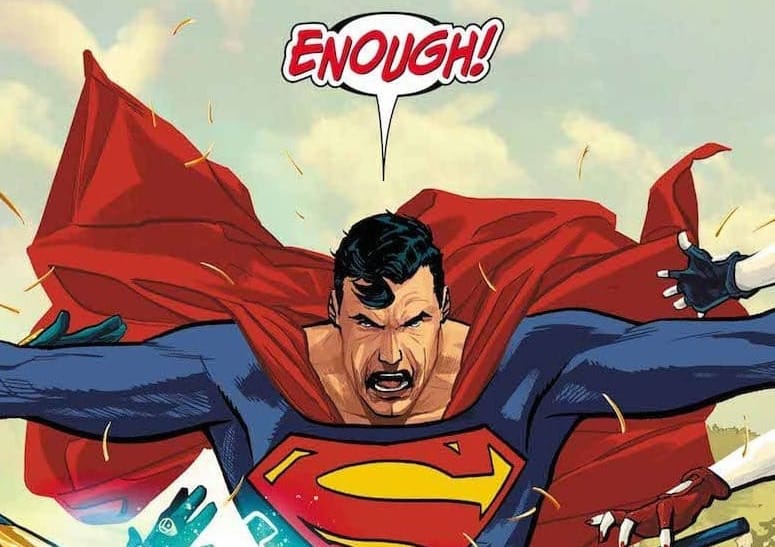

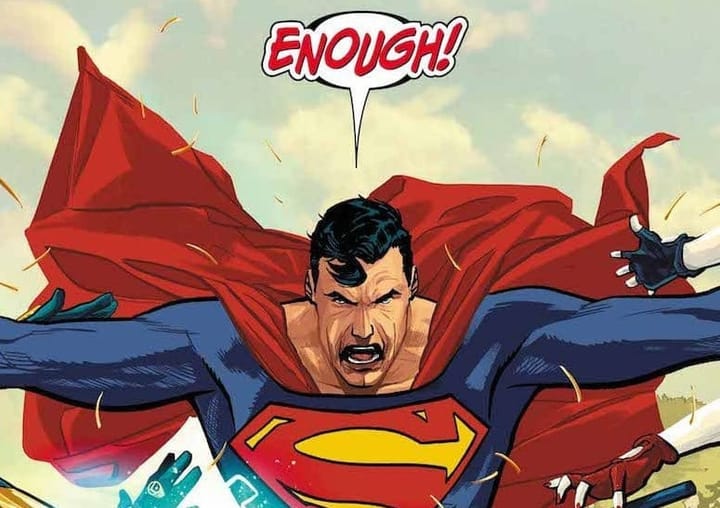

The supers of the DC Universe fill a similar niche that faith leaders, therapists, and your Mom FriendTM do (though “Heroes in Crisis” and Tom King’s work writ-large leans more on the “supers as soldiers” analogy.) They're looked up to, confided in, and expected to be the best of us. They’re not seen as peers by ordinary folks, which in turn, puts them into the position of feeling like they have to project an aura of confidence, knowledge, and general put-together-ness.

And isn’t that the general refrain from fans? Marvel’s supers are just like us but DC’s are embodiments of ideals. Aspirational. More than human. Yet, as more and more stories acknowledge, in private they struggle, and they struggle alone.

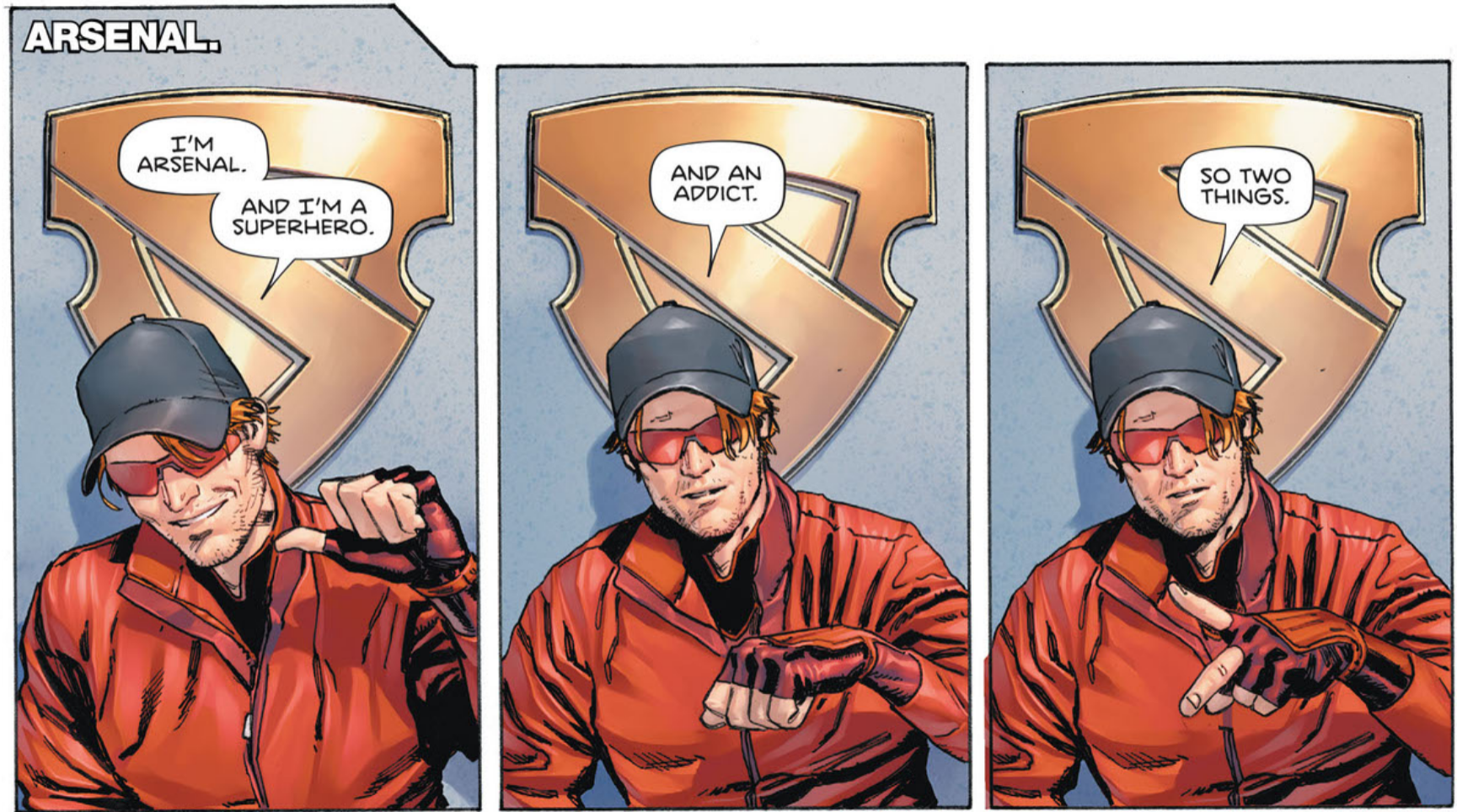

In some ways, this is not a new innovation in the superhero genre. Realism within the fantasy and the seriousness - as opposed to earnestness - of the narratives has been a trend since at least the late 70s: the Bronze Age of Comics, as it were. Roy Harper’s substance abuse in “Green Lantern/Green Arrow” #85 and 86 comes to mind as the Ur-example at DC, though I could be mistaken.

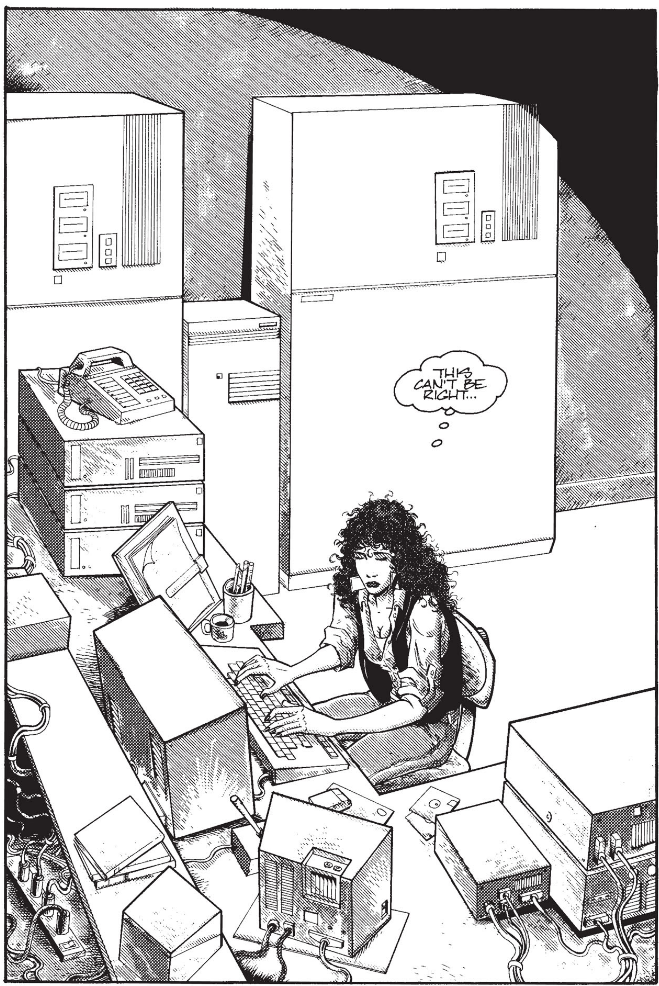

What is innovative in “Heroes in Crisis” however is in approaching the narrative with a realist lens and then asking: “How do these major, traumatic, uniquely difficult situations affect these characters? How does it make them feel? What would they say if they could talk frankly, without fear of judgment or a loss of perceived trust?”

The answers are, predictably, obviously, tough to consider. Superhero books throw a lot at these characters, after all. Even the simplest, silliest conceits belie traumatic events and ideas.

Minor characters like Gnarrk the Caveman questions his place in the universe, time-displaced as he is, and whether he is better off now or then, in issue #5. In that same issue, and throughout the mini, Harley talks about leaving an abusive relationship, hiding her fear of being loved again behind a facade of indifference and clownery, simultaneously recognizing what she’s doing and being unable to reconcile it. The Robins, another minor throughline across all nine issues, all express their fears that they are the one member of the team without an identity unto themselves, or in Stephanie’s case, that they have been forgotten.

Central to this argument is Wally, arguably the most important character in “Heroes in Crisis.” His position as the symbol of hope of the DC Universe per Rebirth saddles him with a uniquely heavy burden. While King & co. seem to discard the well of optimism Wally has always carried to portray it, the questions remain salient.

What does grief look like when your family is gone, you’re the only one who remembers them due to time-shenanigans, and everyone expects you to be “alright” and take on their fears? What happens when you’re afraid to admit you’re hurting and how does that hurt yourself and others more?

Who can you talk to in that situation? Superman may be empathetic (and has shown a remarkable talent for this in the past) but he cannot be there for everyone, all the time, and is certainly not equipped for it. Perhaps a professional, in a setting custom built for helping support the super people who are the support of others, could be just what the Doctor Mid-Nite ordered.

Of course, this then begs the question of what form this support should take. Is it personalized? Group-based? Is it more of a retreat or more medicalized? Who is running the location and how? For King, he sees the answers, and the model, in the confessional.

Let us put aside the religious nature of confessionals for a second - confessionals are, after all, a traditionally Catholic thing to do. Instead, let us consider what they are and what they ultimately do.

The confessional is a place of unburdening, where one goes to talk and to be heard. Where one can confide in another and be unafraid that what they say will end up as gossip, floating free in the world. It is meant to be a place of cleansing, of exorcising. There is also an expectation that one will receive, at the end, methods forward and remedies, but little in the way of feedback or back-and-forth responses.

In this way, it is self-directed, encompassing only what the confessor wishes to offer up which in turn allows them to be radically open and vulnerable. People are often more willing to be messy and deep when they think they are conversing with one who will not converse back. Speak. Respond. React, perhaps. But not converse. It is a craving humans share, this one-sided conversation with an invisible other, like in diaries…or prayer.

Alright, maybe it’s impossible to separate the confessional from its religious, and Catholic, roots and yes, perhaps, in my non-Christian ignorance, I’m overstating the confessional’s roots and appeal. I don’t think it changes what a confessional does or represents nor the reasons “Heroes in Crisis” uses its iconography and format - replacing a priest with an A.I. and the confessional booth with a camera and a room - for Sanctuary.

In picking the confessional, “Heroes in Crisis” is gesturing at a wider practice of externalizing the internal so as to help one understand it, and oneself, better. For some, it is enough, simply speaking their troubles aloud - large or small, chronic or acute, meaningless or profound. For others, something more dialectic is necessary. For still others, an entirely different approach is needed. Sanctuary can be all these things. Or none, as the story dictates.

“Heroes in Crisis” can serve as the model for what didn’t work, acting as the razed ground from which to rebuild and regrow, the soil nurtured by its ashes, reaching towards what else Sanctuary was supposed to be. A place of safety. A place that promises confidentiality. A place of true anonymity.

Liking what you read so far? Want these delivered straight to your inbox or, dare I say it, early? Sign up for a subscription today! Part Three is coming in two weeks but if you're a paid subscriber, you can read this in its entirety right now. Just $1.50 a month and you'll be supporting an independent writer.

If you aren't able to, that's OK as well. I'm just happy you're reading and sticking around.

Comments ()